Brian Stoveken Works on Research to Delay the Process of Aging

Brian Stoveken, a graduate student in the Biology of Aging program, became interested in science after his high school biotechnology program at Middleton High School in Wisconsin.

Brian Stoveken, a graduate student in the Biology of Aging program, became interested in science after his high school biotechnology program at Middleton High School in Wisconsin.

The program worked with a local biotech company to provide educational resources to teachers interested in conducting basic molecular biology experiments with their students.

“It gave me experience propagating and manipulating DNA, and also a fundamental understanding of genetic information,” Stoveken said. “This is essential for what we do in our research.”

Stoveken initially was interested in biomedical engineering and was drawn to the biology of aging after a course his sophomore year.

“It was one of those things that stuck with me. It’s something you bury as a seed inside your mind, but as you get older and as you start to see people in your family get older, or you encounter people who have some of these age-associated illnesses, it becomes much more real,” he said.

With UT Health Science Center’s pioneering research in the field of aging through the Barshop Institute for Longevity and Aging Studies, Stoveken was drawn to the Biology of Aging program offered by the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

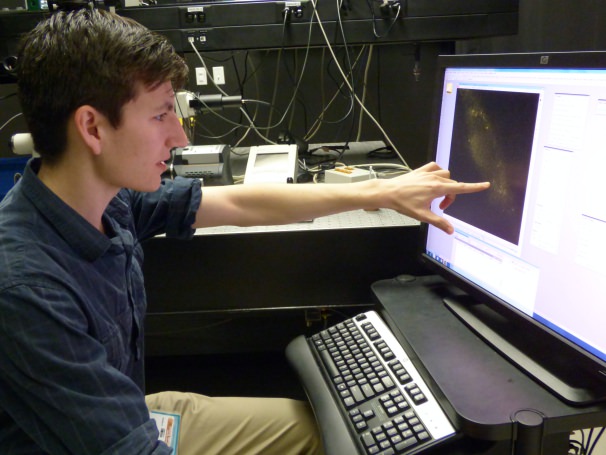

He is currently working on research regarding neurodegenerative diseases in Dr. James Lechleiter‘s lab, specifically looking at the PERK protein and understanding how mutations affect the protein’s activities using super resolution microscopy.

He explained

that PERK is an interesting and dynamic molecule in which heightened PERK

activity is observed in age-associated neurodegenerative conditions, and

mutations in PERK are associated with a neurological disease called progressive

supranuclear palsy (PSP).

“Individual PERK proteins are situated in membranes within cells, and they cluster together in response to stress,” Stoveken said. “This clustering is thought to activate PERK, and super-resolution microscopy lets us see it happen in cells.”

“So if we can watch this happening then we can ostensibly find ways to block it from occurring. We can also understand if PSP-associated mutations cause PERK activity to increase or otherwise alter its behavior in some way as we age.”

Stoveken explained that the long-term possibilities of his research could lead to possible therapeutics.

“Understanding and regulating PERK activity may be critical for treating Prion disease, as well as PSP, Alzheimer’s disease, and several other diseases characterized by aggregation of a protein called tau.” he said.

He explained that he hopes that the work he is doing will make a difference.

“It’s unfortunately a really difficult protein to study but we are starting to make some

progress,” he said. “We really do think that the microscopy approach is a novel

way to study it.

Stoveken explained that in the future, he would like to continue the work he is doing in the lab and also create his own program similar to the one he attended.

“I was lucky to have excellent teachers/mentors, and to spend time in an education-oriented lab group during college and I want to carry this tradition of scientific education forward,” he said.

“I think that there is, and always has been a need to mentor students in the sciences — not to turn everybody into a scientist, but to give people the toolset that a scientific worldview provides so that they can approach problems scientifically,” he said. “There is not a single discipline that I can think of where that wouldn’t come in handy.”

This article was written by Charlotte Anthony, marketing specialist at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at UT Health San Antonio. This article is part of the “Meet The Researcher” series which showcases researchers at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio.

This article was written by Charlotte Anthony, marketing specialist at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at UT Health San Antonio. This article is part of the “Meet The Researcher” series which showcases researchers at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio.