Why Is It So Hard For Us To Achieve Diversity?

Dr. Lydia Villa-Komaroff spoke to a handful of students and faculty at UT Health San Antonio on Oct. 9 about the cognitive processes that interfere with achieving diversity.

Dr. Lydia Villa-Komaroff spoke to a handful of students and faculty at UT Health San Antonio on Oct. 9 about the cognitive processes that interfere with achieving diversity.

Dr. Villa-Komaroff is one of the founding members of SACNAS, the Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science. She is also widely credited as being one of the first female Mexican-American to get a Ph.D. in science in the United States.

“Diversity and underrepresented women in science is a big part of my life because how could it not be,” she said.

Dr. Komaroff explained that women of color are as likely as white women to graduate from high school, start college, and graduate in a STEM field if they complete college.

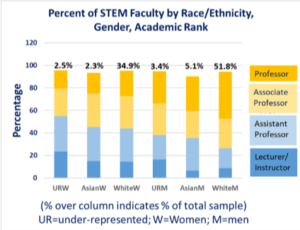

“But if we look at academia, we see that white males are still found at the top as professors or associate professors while women and underrepresented minorities are found as lecturers and instructors,” she said.

She did note that the research has shown that people of color are less likely than white people to graduate from college, obtain a Ph.D. in science/engineering, or obtain a tenure track job in a non-minority serving institution. However, women of color are more likely than white women to get tenure if they are on a tenure track at a research 1 University.

“I suspect that this is because if that woman of color has already gone through all the hurdles, she is a pretty dynamic and likely to succeed despite the obstacles she might face,” she said.

Dr. Komaroff said that women in particular face biases in the workplace including motherhood bias (motherhood provokes very negative assumptions about an individual’s competence and commitment), recall bias (women’s mistakes tend to be noticed more, and remembered longer than men’s) and attribution bias (women’s successes often are attributed to luck or other outside causes: he’s skilled; she’s lucky).

Dr. Komaroff said that women in particular face biases in the workplace including motherhood bias (motherhood provokes very negative assumptions about an individual’s competence and commitment), recall bias (women’s mistakes tend to be noticed more, and remembered longer than men’s) and attribution bias (women’s successes often are attributed to luck or other outside causes: he’s skilled; she’s lucky).

“If you take two women with the same CV and one line is different—“member of the PTA,” you would think they would be ranked the same but all people (regardless of whether the reviewer scoring the candidate was a woman or man, young or old) on average rank the woman who is considered to be a mother as less capable than the one who was not.”

She explained that humans have two systems of thinking. One, which includes our innate survival skills, operates automatically, unconsciously and rapidly.

“This is why when you see a large black or brown man, we all inherently tend to have an immediate association with danger and this is because of our history and culture. We have not yet at as a society dealt with our history.”

System 2 allows us to focus on difficult tasks but this can also blind people.

In a study that was done where participants were asked to watch a basketball game and count the number of passes, they completely missed the man in a gorilla costume who ran across the court in the middle of the game.

In a study that was done where participants were asked to watch a basketball game and count the number of passes, they completely missed the man in a gorilla costume who ran across the court in the middle of the game.

“The invisible gorilla tells us that our allocation of attention is honed by evolution.”

Dr. Komaroff’s advice was to be aware of our implicit biases especially in hiring.

“When a minority faculty candidate comes in, they are thinking about the community they will be joining like ‘what grocery store am I going to go to’ or ‘what church will I join’ or ‘where can I do my hair,’ so perhaps instead of having one day of just full interviews, we could allow the candidate to take half the day to understand the community.”

Although people are well intentioned, Dr. Komaroff said that it was natural for people to surround themselves for people similar to themselves, but we should be aware of our implicit biases. She recommended that people visit the Project Implicit site to take a test.

To see the slides from her talk, click here.

This article was written by Charlotte Anthony, marketing specialist at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at UT Health San Antonio.

This article was written by Charlotte Anthony, marketing specialist at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at UT Health San Antonio.