Aleeza Stephens: I’ve Seen How Brain Damage Can Affect Personality

Aleeza Stephens was a sophomore in high school when her cousin had a football injury. He was diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury affecting his frontal lobe.

Aleeza Stephens was a sophomore in high school when her cousin had a football injury. He was diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury affecting his frontal lobe.

“He’s ok now but it definitely affected his personality,” explained Stephens, a student in the Neuroscience discipline of the Integrated Biomedical Sciences Ph.D. program. “To know that an injury can affect your personality like that spurred my interest.”

Stephens is currently in the lab of Dr. Alan Frazer where she is looking at depression and antidepressant research.

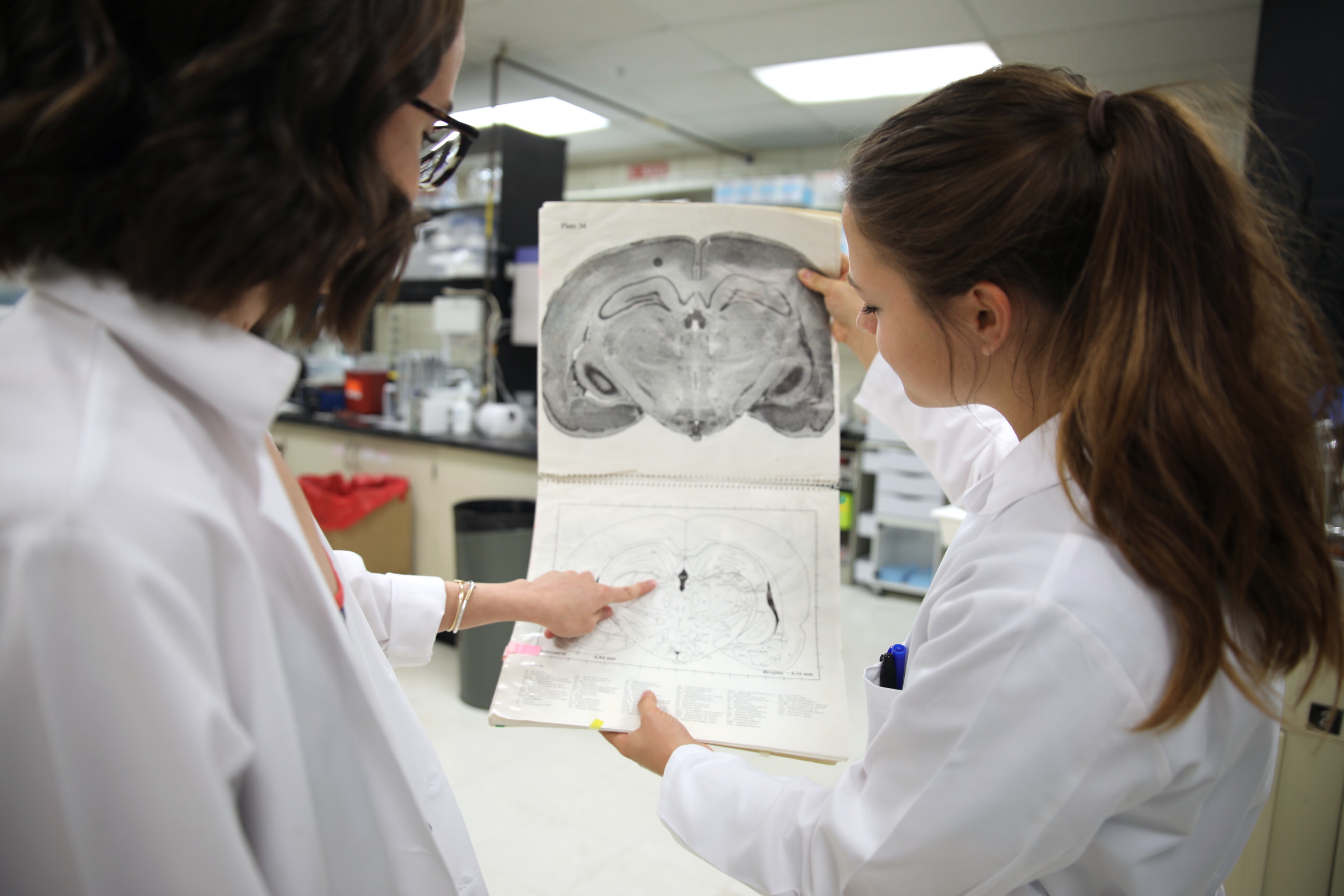

She explained that one of the areas of her research focuses on negative cognitive biases, which are a core component of major depressive disorder. An example of a negative cognitive bias is when a person who used to enjoy an activity now recalls those experiences as negative. This can result in patients with depression no longer being motivated or interested in doing activities they once enjoyed, which is called anhedonia.

“The current treatments for depression aren’t ideal and it’s also challenging to model behavior with rats because rats don’t get depressed like we do,” she said. “A lot of animal models don’t translate to the human condition, especially anhedonia, which is normally modeled with a test measuring rats’ sucrose consumption. The anhedonia seen in humans is more complex and reward expectancies and motivation are likely heavily involved. Therefore, I think it’s important that if we are trying to find new treatments that we find better behaviors to model the human condition.”

“The current treatments for depression aren’t ideal and it’s also challenging to model behavior with rats because rats don’t get depressed like we do,” she said. “A lot of animal models don’t translate to the human condition, especially anhedonia, which is normally modeled with a test measuring rats’ sucrose consumption. The anhedonia seen in humans is more complex and reward expectancies and motivation are likely heavily involved. Therefore, I think it’s important that if we are trying to find new treatments that we find better behaviors to model the human condition.”

In the lab, the rats are trained with two tones and two levers. One tone tells the rat to respond on one lever in order to receive a sucrose reward (positive) and a different frequency tone tells them to respond on the other lever in order to avoid a foot shock (negative). The rats are then presented with a new tone that has a frequency between the two tones they were trained on and which lever the respond on is measured. If they respond on the positive lever, it’s interpreted that they expect a sucrose reward. If they respond on the negative lever, it’s interpreted that they expect a foot shock.

“Normal rats will respond roughly equally on both positive and negative levers in response to the new, ambiguous tone. If we stress the rats, we would expect that they would press the negative lever more often because they now have a negative bias where they expect the foot shock more often than a sucrose reward,” she said.

When asked what she likes most about UT Health San Antonio, she said that she likes her lab environment.

“I really like that it’s a small lab and it’s easy to be collaborative. Dr. Frazer is really great because he’s helped me to improve my presentations. He’s also really supportive and and respects and listens to my input which is nice,” she said.

Besides research, she loves gardening and cats.

“I have a lot of house plants and decorative patio plants because it gives me something to do,” she said. “I like the responsibility of keeping them alive.”

Aleeza will be participating in the candidacy ceremony this August. In the future, she would like to continue to work on developing different animal behaviors to model psychiatric illnesses.

This article was written by Charlotte Anthony, marketing specialist at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at UT Health San Antonio. This article is part of the “Meet The Researcher” series which showcases researchers at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio.

This article was written by Charlotte Anthony, marketing specialist at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at UT Health San Antonio. This article is part of the “Meet The Researcher” series which showcases researchers at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio.