Dealing with Grief During Grad School (and a Pandemic)

It’s no secret that grad school is often associated with unparalleled amounts of stress. From failed experiments, lack of a “work-life balance,” or professors that go missing in action when students are waiting for edits on manuscripts or thesis papers, the ins and outs of graduate student life are inherently taxing and demanding.

There are even social media pages that post nothing but memes related to all the different types of stress and anxiety that are experienced while in a graduate program. This perpetual dread that graduate students feel is almost readily accepted within the academic community, with most accepting that succumbing to this stress is an inevitable fact of “grad life.” Now more than ever, it is important that the mental health of our graduate student body is no longer ignored, as a recent survey among 5,000 U.S. based STEM graduate students reported an increase in those who screened positive for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This conversation has been brought up during this COVID-19 era, where many people are experiencing severe mental health crises in a world where we are self-isolating and social distancing to stop the spread of the coronavirus. We have been hearing the words “unprecedented times” and “new normal” for the last six months, and although the adjustment to this type of living has been no issue for some, there are those that are dealing with so much more than just learning to live with mandatory mask requirements and virtual learning. The evening of March 31, when the pandemic was just starting to gain national attention and city-wide shutdowns were commencing across the country, I got a call from home that ripped my heart out and would completely change my life. My father, whom I had just talked to a couple days prior, had a heart attack while at work and had passed away.

Immediately booking a flight for the next afternoon, I spent the whole night awake lying on my couch. I desperately wished for this to be a very vivid nightmare that I would wake up from and quickly brush off. I waited until the next morning to call my supervisor (PI), not asking for permission to go, but informing him firmly that I was flying home to grieve with my family and manage his arrangements and estate. Although I know this is not always the case, my PI was extremely understanding and supportive and allowed me ample time away from lab – something I am truly grateful for.

As I am the eldest daughter and my parents having been divorced for 16 years, this meant I was responsible for everything from this point on. From handling decisions about his remains, completing and filing his taxes, moving forward with probate to transfer cars and property over to my sister’s and my name, and other countless steps needed to be taken following his death, I quickly became overwhelmed and realized, as a 26-year-old, I was completely unprepared for this entire set of procedures and responsibilities. Even though I had not been thinking readily about the pandemic, it soon became evident that it would play a large part in my journey handling my dad’s passing. Handling arrangements and the transfer of my father’s accounts was hindered by the COVID-restrictions. Most businesses were limiting in-person interactions, which meant that most conversations and transactions were conducted over the phone, where we would be put on hold countless times for long waiting periods.

My family was also not allowed to see my father at the coroner’s office, meaning that I did not get to see him at all before his cremation. With the pandemic at its height, having a memorial to bring together people who wished to pay their respects was also impossible. That lack of comfort from our extended family and friends was something I had not envisioned when losing a parent. I had imagined that when I did lose a parent that I would have all my closest family members and friends surrounding me, lending a shoulder to cry on and people who knew my dad that could comfort me by sharing their favorite memories of him. It was for this reason that I feel, to this day, that I have yet to fully and properly accept and mourn his passing, feeling as though he vanished into thin air rather than died.

While I was home those first few weeks, my thoughts were consumed by the loss of my father and my depression was clearly manifesting. I did not sleep or eat for those first couple of days. But even as time passed, my entire sleep schedule was turned on its head. I relied heavily on over-the-counter sleep aids, which persisted for several months even after I flew back to Texas. When the days weren’t spent dealing with the fallout of my father’s death, I could be found in bed or on the couch. All my motivation for doing anything else productive was completely obliterated. This was especially concerning because my father’s passing did not negate the fact that I was still in grad school and had obligations to move forward with my research. I still found myself feeling guilty for taking so long to shake my depressive state and feel useful to the lab. Completing some analysis for an upcoming manuscript remotely from California helped me jumpstart my motivation of returning to the hustle and bustle of a research-based graduate program.

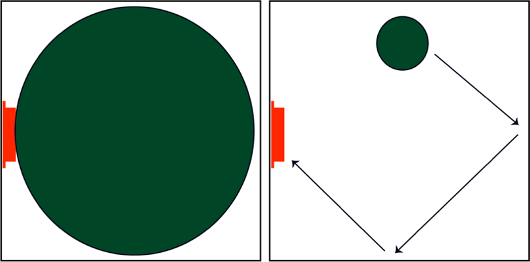

However, getting back into a rhythm once I returned to San Antonio was extremely difficult; one analogy that I thought was apt is the “ball in a box.” When grief is new, the ball is big and cannot move within the box without hitting the button, which represents the pain we feel when we grieve. Over time, the ball will get smaller, but as it moves randomly around the box, it will eventually hit the button. Although it hits the button less often, the pain we feel is the same intensity as it was previously and can be brought on without warning.

I found myself dwelling on certain aspects of my father’s passing that I could not change, and it was for this reason that I sought out professional help through an Employee Assistance Program and talked with a therapist through Zoom appointments. Thankfully, I was able to speak with the same person while I was in my hometown and after I came back to Texas. Most of our time together was spent with me venting about how the pandemic had affected the circumstances surrounding his death, as he was alone in the breakroom due to work from home orders when he collapsed and was not discovered until hours later. In my head, I knew that these safety measurements were necessary to mitigate the spread of COVID, but I couldn’t help but wonder if my dad would have lived if he received medical attention sooner.

We also discussed my inability to fall asleep, and she encouraged me to see a physician because I was worried about my dependence on sleep aids and how they would affect me going back to work. The conversations we had during my sessions were extremely helpful and ones that I would have normally discussed with my close friends; however, because of the extended period in which everyone was social distancing, there came a point when communication between these friends began to dwindle. In this time of social distancing, it is imperative to still keep an eye on your friends or reach out, especially if you know they have suffered a loss.

During these devastating times, it is important to be “selfish.” Allowing yourself to step back and remove yourself from the stresses of grad school to focus on grieving and getting your life back together should be your highest priority and should not make you feel guilty in any way. Grad school is already so demanding that dealing with a death, whether it was expected or not, will only add to the anxiety you feel. If going through this experience (during a pandemic) has taught me anything, it is this:

- Avoid comparing yourself to others (how they grieve, how fast they deal with their grief, etc.)

- Don’t be afraid to seek help/reach out to others

- Celebrate the small steps in your recovery

- Know that healing will take time

I was fortunate that my father’s work offered me counseling, but if they hadn’t, I would at least have my resources at the Graduate School to get me through the toughest time in my life. If you are feeling stressed, anxious, or are dealing with any type of personal loss, do not hesitate to utilize the Student Counseling Center– that is what it is there for.

Other useful resources are listed below:

National Suicide Prevention Hotline – 1-800-273-8255 (available in English and Spanish)

The National Grad Crisis Line – 1-877-472-3457

The National Grad Crisis Line helps graduate students reach free, confidential telephone counseling, crisis intervention, suicide prevention, and information and referral services provided by specially trained call-takers. All counselors have completed training to understand the unique issues faced by graduate students.

About The Author

Nicole is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Integrated Biomedical Sciences at UT Health San Antonio. She is currently working under Dr. Myron Ignatius using the zebrafish model of rhabdomyosarcoma to elucidate mechanisms of growth and metastasis, as well as potential treatments. She is focused on finding a career in science communication, either as an editor for a scientific journal or as a science writer. Read an article about Nicole– “Nicole Hensch: From Dispensing Medications to Designing Medications.”

Nicole is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Integrated Biomedical Sciences at UT Health San Antonio. She is currently working under Dr. Myron Ignatius using the zebrafish model of rhabdomyosarcoma to elucidate mechanisms of growth and metastasis, as well as potential treatments. She is focused on finding a career in science communication, either as an editor for a scientific journal or as a science writer. Read an article about Nicole– “Nicole Hensch: From Dispensing Medications to Designing Medications.”

The “Beyond The Bench” series features articles written by students and postdoctoral fellows at The University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio.